The loss of most pre-1901 census records in Ireland means that it can be extremely difficult to locate your Irish ancestors in the 19th century. So, alternative records need to be found. One very useful resource is Griffith’s Valuation. This was a mid 19th century survey of all property and land on the island of Ireland. This post looks at the component parts of Griffith’s Valuation.

What was Griffith’s Valuation?

Sir Richard Griffith

The Primary Valuation of Ireland was a detailed survey of all property and agricultural land. It was supervised by the prominent geologist, Sir Richard Griffith. The Valuation was published separately for each county between the years 1847 and 1864 as follows:

- Antrim 1861-2

- Armagh 1864

- Carlow 1852-3

- Cavan 1856-7

- Clare 1855

- Cork 1851-3

- Derry (Londonderry) 1858-9

- Donegal 1857

- Down 1863-4

- Dublin 1847-51

- Fermanagh 1862

- Galway 1855

- Kerry 1852

- Kildare 1851

- Kilkenny 1849-50

- Laois (Queen’s) 1851-2

- Leitrim 1856

- Limerick 1851-2

- Longford 1854

- Louth 1854

- Mayo 1856-7

- Meath 1855

- Monaghan 1858-60

- Offaly (King’s) 1854

- Roscommon 1857-8

- Sligo 1858

- Tipperary 1851

- Tyrone 1851

- Waterford 1848-51

- Westmeath 1854

- Wexford 1853

- Wicklow 1852-3

The purpose of the survey was to determine the value of properties and therefore the amount of tax that could be charged on them. This system continued to be used until the 1970s in the Republic of Ireland.

There are four components to the survey, all of which are useful to the family historian:

- The printed valuation books

- Contemporary maps

- Valuation office books

- Revision books

I’ll go through each of the components below.

Why the Griffith’s Valuation is important for genealogy

On 28th June 1922, during the Irish Civil War, there was an explosion and fire in the Public Records Office in Dublin. Many priceless Irish genealogical records were lost including Wills and Title Deeds, Church of Ireland parish registers, census returns and other records going back seven centuries.

Apart from a few fragments, the census returns of 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851, were lost. The 1861 and 1871 returns had already been destroyed after they were taken. And, the 1881 and 1891 returns were pulped during World War One. This means that almost no 19th century Irish census returns exist now.

For information on the very few 19th century census records that do survive see: Irish Genealogy Records: Fire and Reconstruction.

With the loss of most census records, the Griffith’s Valuation is the only (near) complete resource that shows where people were living in mid 19th century Ireland. Genealogists often refer to it as a census substitute, but it isn’t really.

The survey only records the name and location of the head of a household. Details of the rest of the family are not shown. However, as the records were regularly updated, it is possible to trace a property forward to the 1901 census or vice versa. The revision books show when a property changed hands and the name of a new tenant. This is very useful to do if the property stayed with the same family.

Printed Valuation Books

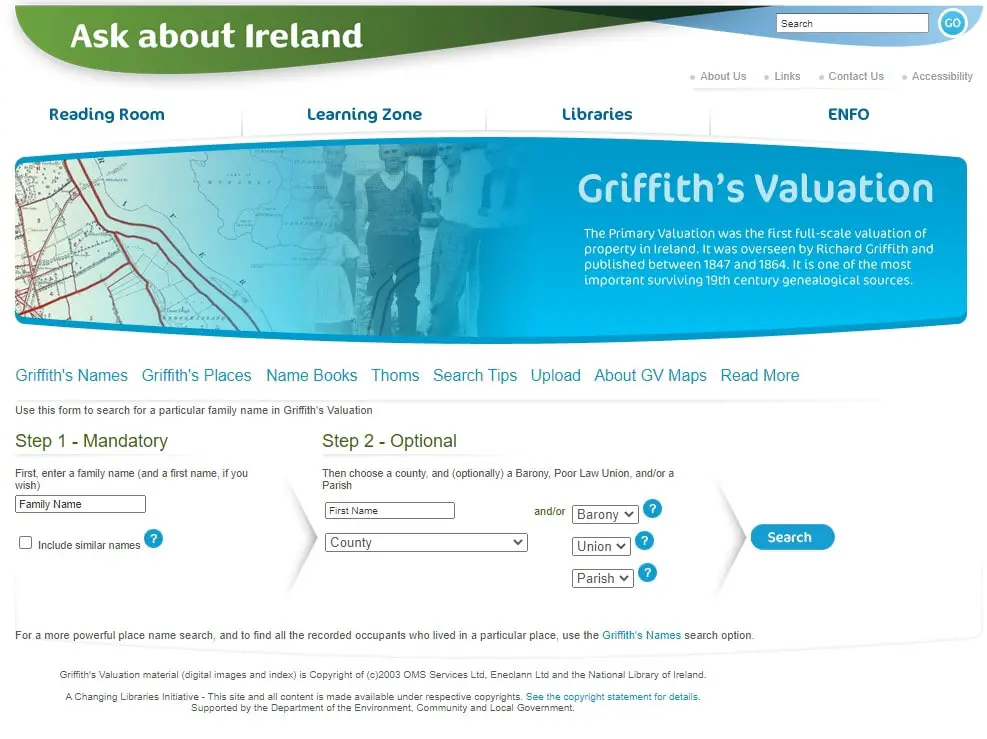

The main part of Griffith’s Valuation are the printed books. These can be accessed for free on the Ask about Ireland website. This resource is a project of Ireland’s public libraries, archives and museums in association with the Government.

Griffith’s Valuation main page

Once on the website, you can either search by person or by place. Select either “Griffith’s Names” or “Griffith’s Places” from the secondary menu.

If searching by name, you need to enter the exact spelling as it appears in the book. So, you may want to enter part of a family name in “Step 1” and then check the “Include similar names” box. For example, if I search for Gowan and check the box, I’ll get Gowan, McGowan, MacGowan and M’Gowan.

Alternatively, if you know the parish where your ancestor lived, you can search by place to get a list of all the local tenants.

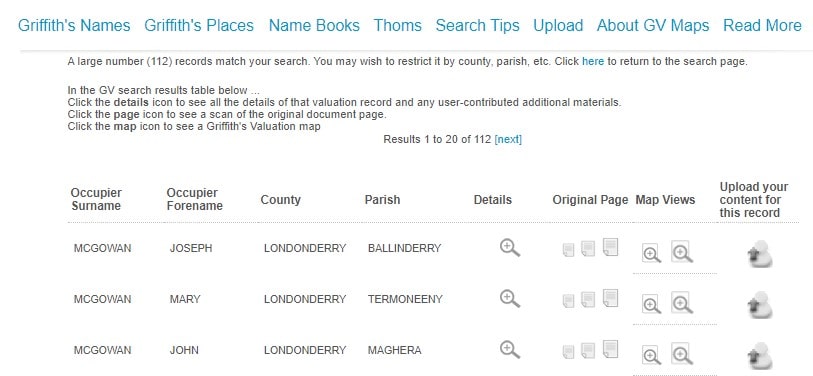

Search Results

The results page will show the name of an occupier/s, county and parish. Clicking on the “Details” icon will give you a transcription of an entry. You can access the original page by clicking on the small, medium or large icon. You can also see the associated map by clicking on one of the map icons (see below).

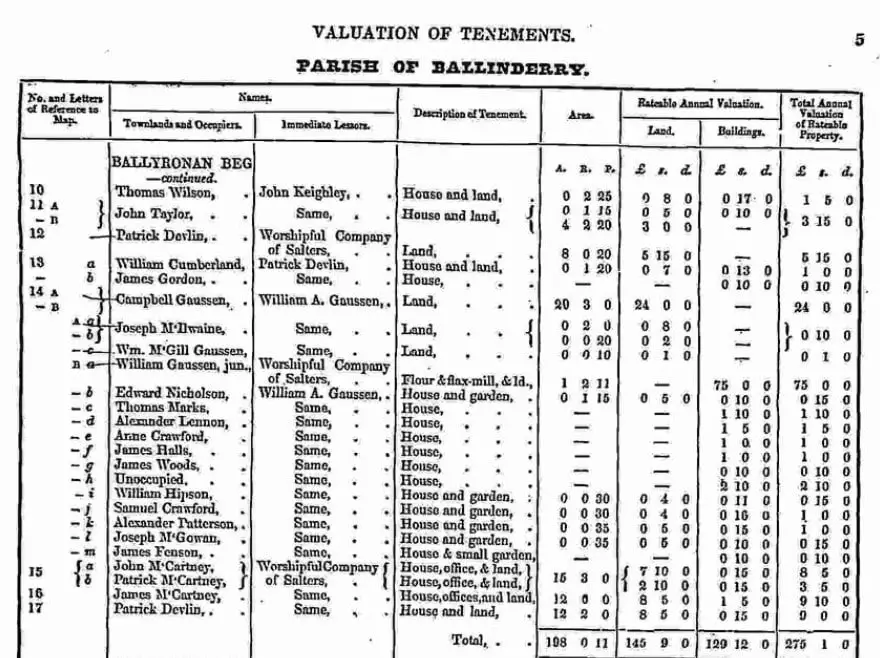

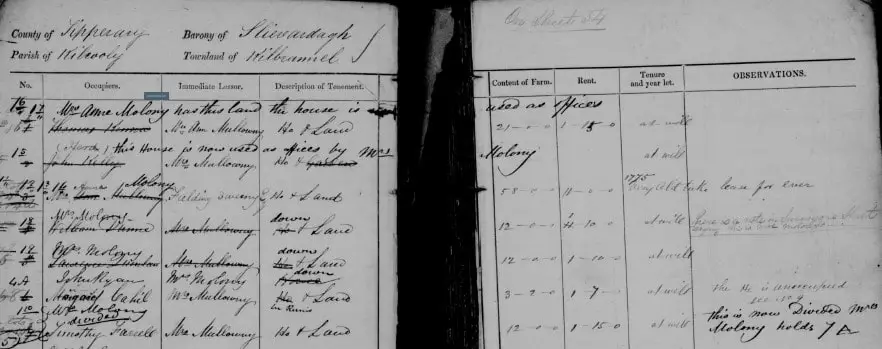

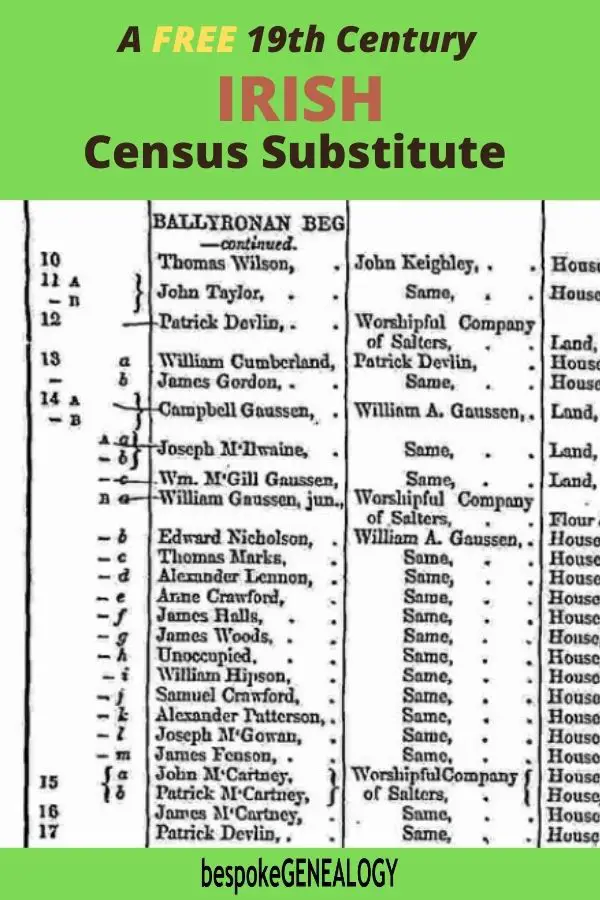

Let’s have a look at part of a page from the Griffith’s Valuation. This is from the parish of Ballinderry in County Londonderry:

Griffith’s Valuation Sample Page

The first column of numbers and letters reference the associated maps (see below). The numbers represent lots. These are shown consecutively and are in the order an area was surveyed. Capital letters after a number show separate properties within a lot. For example, lot 11 is divided into two properties (A and B), both occupied by John Taylor.

Lower case letters represent a single property held by two or more people. Lot 13, for example, is occupied by William Cumberland and James Gordon who each pay rent to the landlord.

If there is a bracket in front of lower-case letters (as in lot 15), then the listed occupiers are jointly responsible for the rent.

The 2nd and 3rd columns show the names of the tenants and landlords.

The description of the property is shown in the 4th column. Note that “office” refers to an unoccupied building such as an out-house, usually used for storage.

The area of the property is shown in column 5. The units of measurement were acres, roods and perches. There were 4 roods to an acre and 40 perches to a rood.

The ratable value of the properties is shown in the last three columns in pounds, shillings and pence. Before decimalization, there were 20 shillings to the pound and 12 pence to the shilling.

Tax was levied at so many pence to the pound. So, if the tax was 5 pence to the pound and the property’s ratable value was 4 pounds, then the tax due would be 20 pence or 1/8d (one shilling and 8 pence).

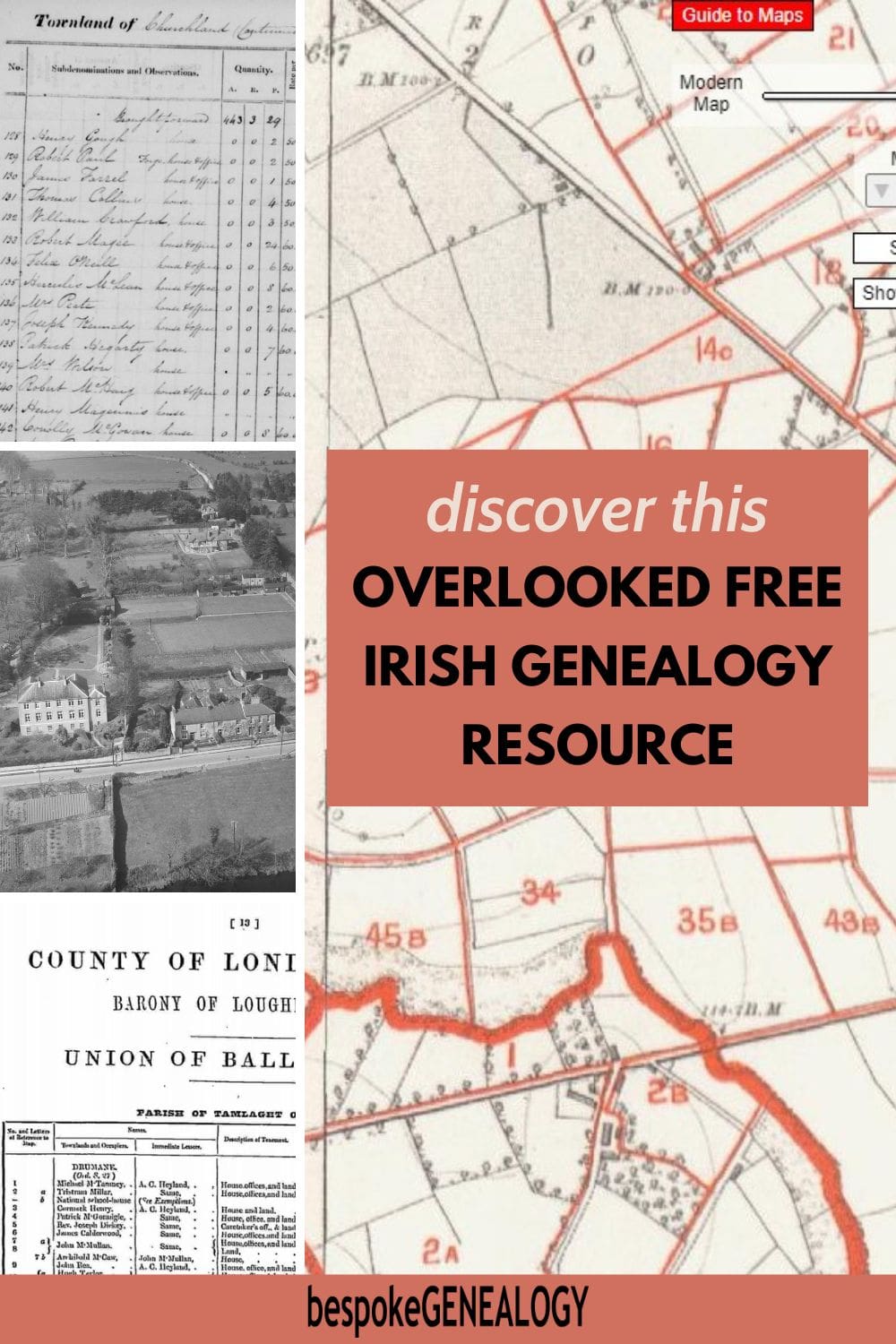

Maps

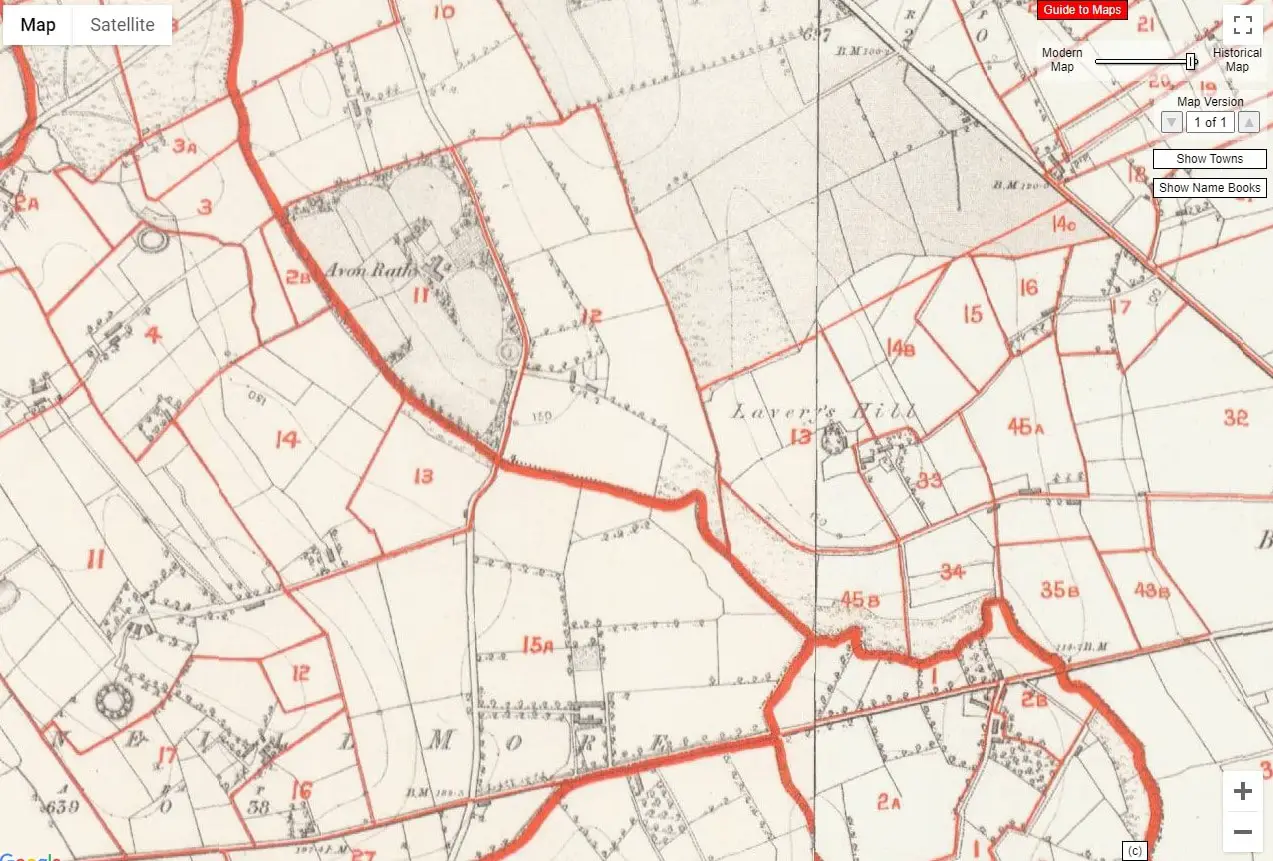

Once you have found your ancestor’s entry in the valuation books, you can find the property on the associated map. Make a note of the map reference and click on one of the map icons in the search results.

The relevant area of interest is shown in a red box. Zoom in to find the property. These maps are near contemporary Ordnance Survey maps:

Griffith’s Valuation Sample Map

By using the slider control on the top right-hand corner, you can move to a modern map. You can also switch to satellite view to see if the property still exists. This is useful if you’re planning a visit.

Valuation Office Books

The work involved in creating what we know today as Griffith’s Valuation was extensive. It required an army of valuers and surveyors and began in in the mid 1820s. Many of the hand written books used have survived and are available to access for free on the National Archives of Ireland website.

It is worth consulting these books as they can contain additional information, not found in the printed books. There were four types of office books:

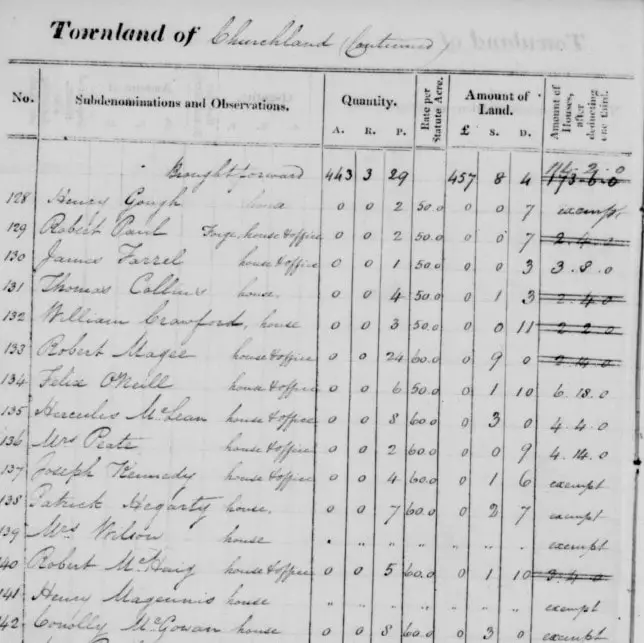

Field Books

Field book extract

These books date between 1830 and the mid 1850s and contain information about the valuation of agricultural land. More information can be found here.

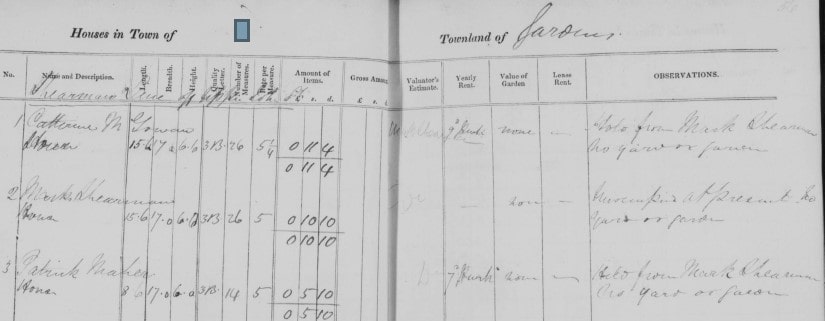

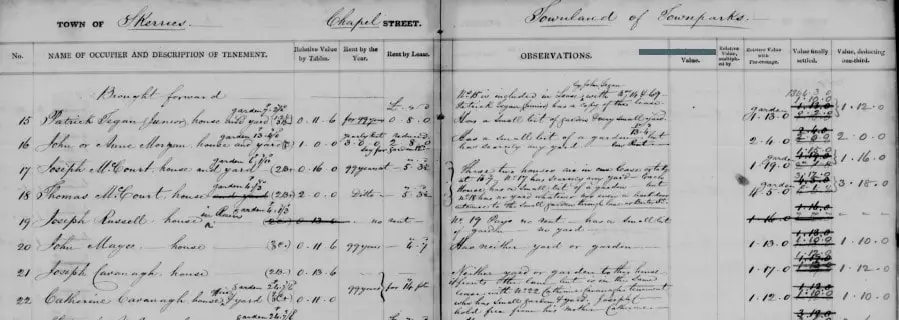

House Books

House book extract

House books date from 1833 to the mid 1850s. They contain valuation information on houses and buildings. Detailed information about this resource can be found here.

Tenure Books

Tenure book extract

Tenure books were made between 1846 and 1858. They contain information about how buildings relate to agricultural land. They also contain information about occupiers. See this page for more information.

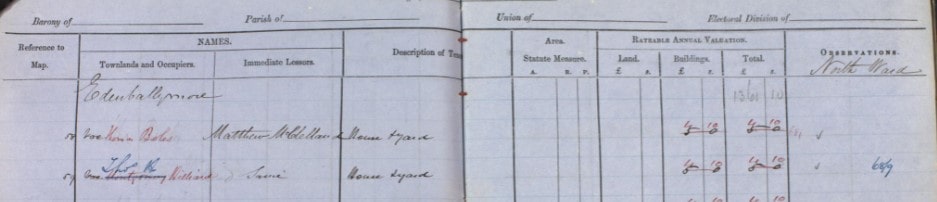

Quarto Books

Quarto book extract

These books date from 1839 to 1859. They should be used in conjunction with the House books as they record subsequent changes. The Observations column can contain a lot of useful information. You can find more information about these books here.

Valuation Revision Books

Griffith’s Valuation formed the basis of local property tax in Ireland until the 1970s. This means that property information was kept up to date. So, Valuation Revision Books were used to record changes.

Revision book extract

Where to find Revision Books in the Republic of Ireland

The Valuation Revision Books for the Republic of Ireland are held in the Valuation Office in Dublin. Unfortunately, at this time, they are not available online. They can only be accessed by visiting the VO in person.

However, there is a project underway to digitize these records. This should be complete at the end of 2020. So, hopefully, the records will be placed online at some point in the future. I’ll update this post when they are.

Where to find Revision Books in Northern Ireland

The good news is that the Valuation Revision Books for the six counties of Northern Ireland have been digitized. They can be accessed free of charge on the PRONI (Public Records Office of Northern Ireland) website.

Happy researching!

For more Irish genealogy, check out the following pages:

And for further reading on Irish genealogy, I recommend these books:

Please pin a pin to Pinterest:

Census Form N, last column refers to Form M. can’t find any examples of Form M. Any suggestions?

I’m not aware of an Irish census Form M. If you look at the About 1901 and 1911 censuses on the National Archives of Ireland website, these were the main forms: A, B1, B2 and N. In addition, there were some extra forms, depending on the type of institution: B3, E, F, G, H, I, K, C and D. Full details are here: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/help/about19011911census.html#whatcontain

Cheers