If you have emigrant ancestors here are 10 tips for finding them. As well as looking at the types of documents that can give you clues, I also look at some great resources. So here are the 10 tips.

Tip 1; Gather information from your family

The best place to start looking for your emigrant ancestors is to talk to any living relatives. As well as your immediate family, contact cousins if possible. The first task is to see if any relatives know who the migrating ancestors were and where they came from. You should also try and find out other information about ancestors such as:

- Full names

- Where deaths occurred, dates and places of burial

- Marriage dates and places

- Names of spouses including maiden names if applicable.

- Children’s names and places of birth

- Occupations and places of work

- Military service; which service, regiment, ship or squadron

- Schools and colleges attended

- If there are any newspaper clippings or photographs.

- If any family member has already done any family research.

- If they have any relevant documents that you can copy (even if it’s just with your phone)

For more on interviewing relatives, see: Family Interview Questions and Tips

If you’re fortunate, you’ll find a relative that has a family Bible containing useful information including the place where the family came from.

Tip 2; Thoroughly research the family tree in your home country

I would always recommend thoroughly researching your family in your own country before looking for overseas records. It’s important to also research indirect relatives as well. This will increase the chances of finding a document that gives a clue to the place of origin of your family.

Tip 3; Find vital records

Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths started in most developed countries in the 19th century. The amount of information recorded varies between jurisdictions. In the US, for example, the amount of family information recorded varies a great deal between the states.

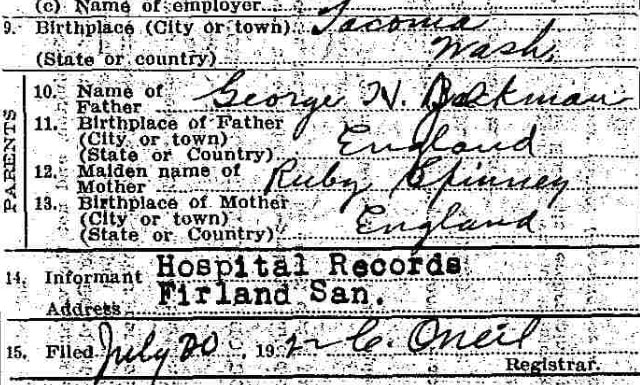

Often, when you find the ancestors who emigrated from their home country, their country of birth will be recorded on some records. Washington State for example records names and birthplaces of parents on death records. This example from 1922 lists the parents of Walter Jackman as being born in England.

Walter Jackman Death Record, extract, 1922.

If you’re lucky, a record will list the actual town of birth of an immigrant parent:

John Campbell death record extract, 1930

This example from 1930, also from Washington, shows that although the mother of the deceased is just listed as being born in Ireland, the father’s place of birth is more specific. He’s shown as being from the city of Liverpool.

So, this is why it’s important to find the records for siblings as well as the direct lines. You might get lucky with a specific place of birth on one of them.

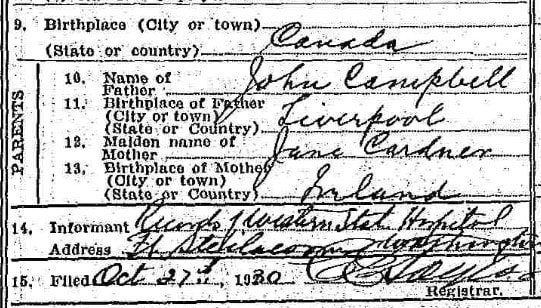

Some Marriage records will show the birthplaces of both the couple and their parents like this 1914 example from New York:

Smith marriage record extract, 1914

In this case, both parents of the groom are recorded as being born in England.

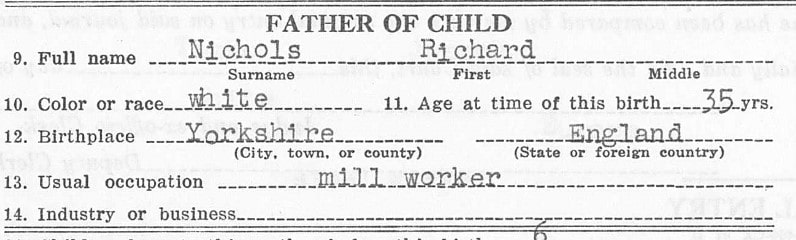

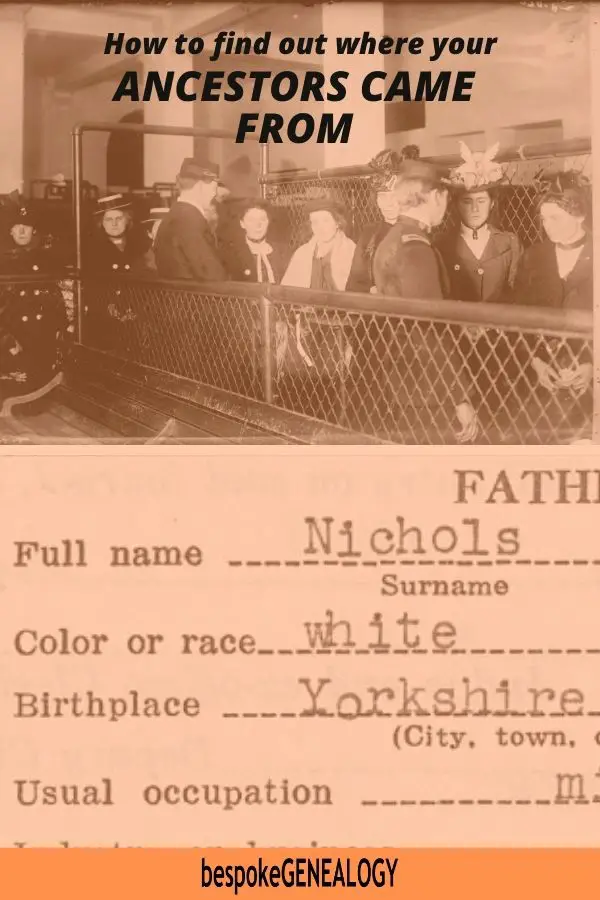

Finally, some birth records will show the birthplace of a child’s parents. Here’s an example from Ohio:

Patrick Nichols birth record extract, 1902.

This 1902 record gives the country and county of birth of the father, as well as his age, which is very useful.

Incidentally, all of these vital record examples were found for free on Family Search.

Tip 4; Look for newspaper articles

Newspapers are an under-used resource in genealogy in my view. This is a pity as they can be rich with great information and are especially good for finding your migrating ancestors. Obituaries are probably the most useful for discovering where your ancestors emigrated from.

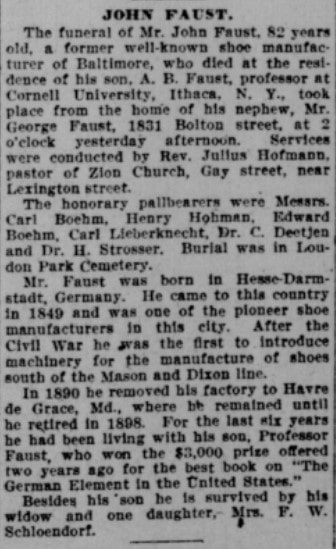

Here’s a great example from 1910:

From the Baltimore Sun, 29 December 1910.

This obituary states that John Faust was born in Hesse-Darmstadt in Germany in 1849. This clipping is especially useful as it mentions three other members of Mr Faust’s family as well as giving details of his career. It also records the church where the funeral took place.

For more on this resource, see: Where to find Free Online Historical Newspapers

Tip 5; Find census records

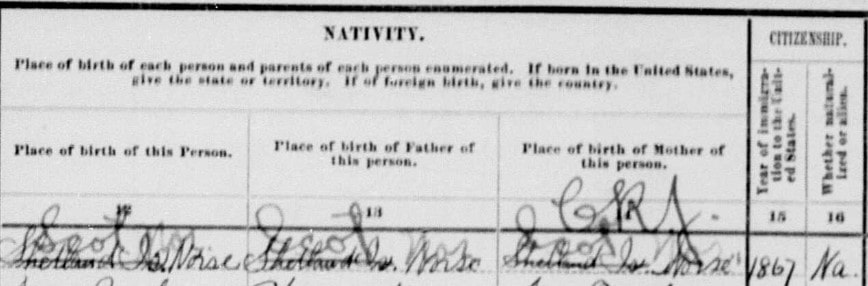

If your ancestors emigrated to the US in the 19th or 20th centuries, census records should help you. The returns from the late 1800s onward record the place of birth of an individual and of his or her parents. Usually this is just a country, but sometimes you see some extra information:

Extract from the 1910 US census

In this example, from 1910, the enumerator originally recorded the Shetland Islands as the place of birth for an individual and his parents. It looks like this was later crossed out and Scotland was written over the top.

The year of immigration is recorded as well, so this may help in finding other documents.

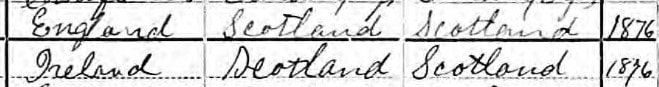

A very useful aspect of these census returns is that they also record the place of birth of parents. This is especially helpful if the parents didn’t come to the US. This next example from 1900 is interesting as whilst this couple were born in England and Ireland, their parents were born in Scotland:

Extract from the 1900 US census

So, this document can help you follow the trail back to your family’s country of origin.

The example above highlights that emigrants did not always take a direct route to their final country. I have seen many instances of this.

The Irish, for example, would often go to England first, to find employment or to escape the frequent famines. They would stay there for a few years and then maybe get an assisted passage to Canada. Again, they would stay for a few years, or even a generation or two, before the family would finally settle in the US.

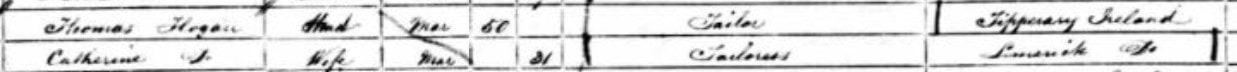

You need to follow the trail backwards. English census returns were not as detailed as in America. Usually if a person was from Ireland, only the country would be recorded. However, sometimes an Irish county is listed, as in this example from 1861:

Extract from the 1861 England census

For more information on the British census see: The Complete Guide to the British Census

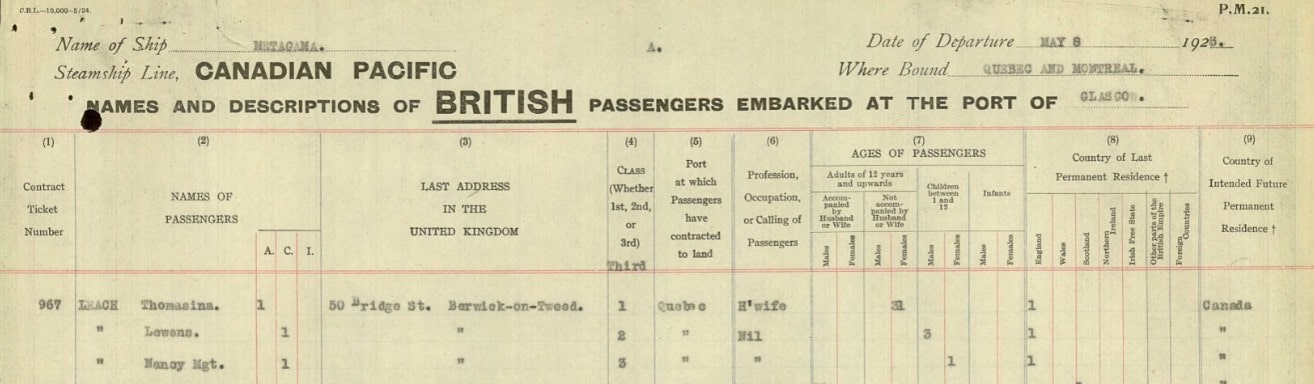

Tip 6; Find passenger lists

Passenger lists vary depending on the shipping line, period in time or the destination. Later ones tend to show more information. But it’s always worth trying to find them for your emigrating ancestors. This Canadian Pacific example from 1925 is especially good as it gives the exact former address of an emigrating family:

Extract from a 1925 Canadian Pacific passenger list

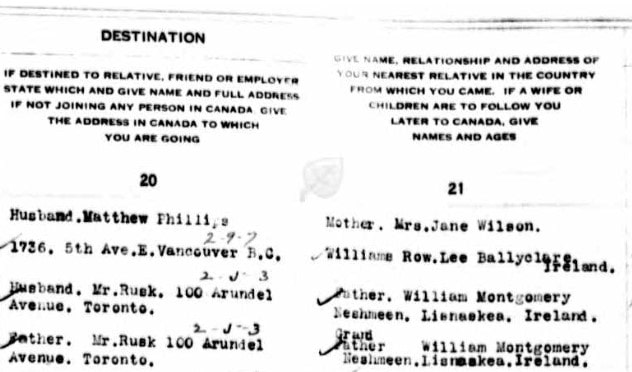

Tip 7; Find immigration records

Official immigration and naturalization records can yield important information if you can find them. Again, the amount of information recorded depends on the jurisdiction and the time period. This Canadian example from 1924 gives names and addresses of relatives in Ireland:

Extract from a 1924 Canadian immigration record

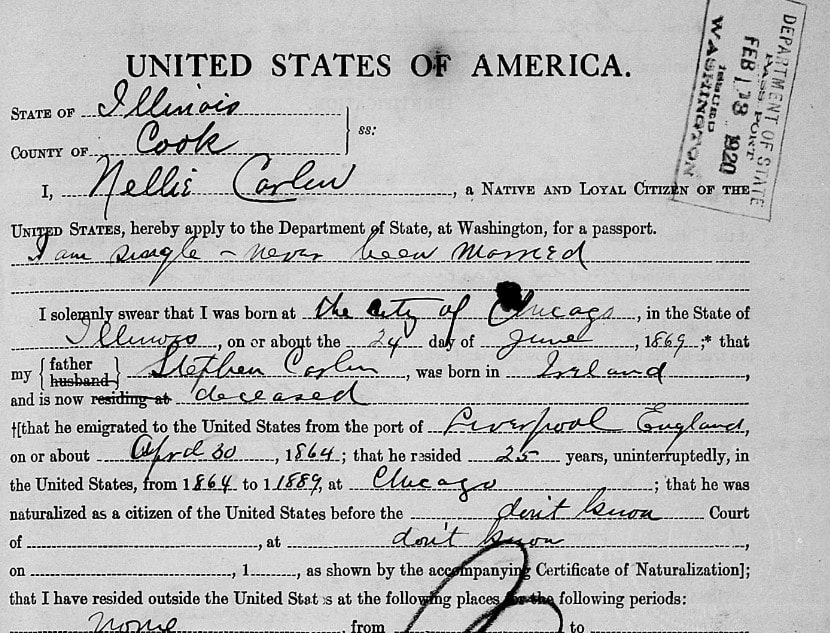

Tip 8; Find passport applications

Very often immigrants would often want to visit their home country to see relatives. They would therefore need to apply for passports. This 1920 example records the name of the applicant’s father and shows that he was born in Ireland. It also states that he emigrated to the US from Liverpool in 1869:

Extract from a 1920 US passport application

Census records as well as various immigration records can be found on Findmypast, Ancestry and Family Search, as well as some of the other sources listed in Tip 10.

Tip 9 Fully research siblings, spouses and neighbors

Don’t limit your research just to your direct lines. You’ll increase your chances of finding a document that records an actual place of origin by looking wider. Find records for all the brothers and sisters of your direct ancestors. The same goes for spouses. Often marriages were arranged and families knew each other in the old country.

If you get stuck and you can’t locate an exact place of origin for your family, look at neighbors. Very often immigrants would settle with people they knew from their original community. So, look at the neighbors on census returns. If they’re from the same country, trace their families and see where that leads.

Tip 10; Find other record sources

Findmypast

This subscription site probably has the best collection of British and Irish records, including travel and migration resources.

Family Search

This free database site has huge collections of vital records and many other sets from around the world.

Ancestry

Ancestry has extensive collections of travel and migration records from many countries.

Libraries and Archives Canada

Libraries and Archives Canada is the nation’s repository, based in Ottawa. The site has several collections of interest to family historians with Canadian connections including census, military and land records.

There’s an extensive collection of immigration records including passenger lists, border entries and deportation records. Many of these sets can be accessed online, free of charge; although some take a bit of work to get to. You may have to look up someone on an index, get the reference numbers and then go to another page to find the scanned microfilm and browse it until you have the record you want. It’s well worth the effort though as many of these records contain priceless genealogical information.

Even if your ancestors were immigrants to the US, you may still find them here. Many US immigrants went to Canada first as the passage was often cheaper or subsidized. They may even have settled in Canada initially and stayed for a few years before heading south. If you’re lucky, you’ll find both the immigration record into Canada and then the border crossing entry into the US.

British Home Children

Between 1869 and 1948, over 100,000 children were sent to Canada from Britain by organizations like the Salvation Army and Dr. Barnardo’s Children’s Homes. These children were used as domestic servants and farm workers. British Home Children is the official website of BHCARA (the British Home Children Advocacy and Research Association) and aims to create a registry of the immigrant children. More information about these children can also be found on British Home Children in Canada.

National Archives Australia

If your ancestors emigrated to Australia, this is the place to start to look for documents.

The National Archives (UK)

The National Archives in London has millions of records covering 1000 years of history. Only a small proportion of collections can be accessed online, either directly or via other database sites. Most records can only be viewed by visiting TNA in person.

However, it is still worth visiting the website for the many research guides that can help you with your family history. You can also use the Discovery page to search TNA and 2500 other archives across the UK to find out what records are available and how to access them.

These are the TNA online migration record sets:

- Alien arrivals

- Alien entry books

- Aliens’ registration cards 1918-1957

- Naturalisation case papers 1801-1871

- Passenger lists

These records are either pay per view on the TNA site (free during the Coronavirus lock down) or accessed via a subscription site.

Ellis Island Passenger Arrival Database

Go to the Ellis Island Database

This is the database of immigrants who arrived at Ellis Island, New York and contains 65 million passenger records.

Castle Garden

Go to New York Passenger Lists, 1890-91 on Family Search

Before Ellis Island was set up, immigrants coming into New York would arrive at Castle Garden. This database contains names of 13 million immigrants who arrived between 1820 and 1891.

The Scottish Emigration Database

Go to the Scottish Emigration Database

This site contains records of over 21,000 passengers who embarked at Scottish ports headed for non-European destinations between 1890 and 1960.

The Highland Clearances

This website has names of Scottish emigrants who headed to various destinations around the world, especially North America. It tells the stories of these people and has a database containing the names of many individuals.

Documenting Ireland: Parliament, People and Migration

If your ancestors were from Ireland, it is well worth having a root around these collections. This site is a virtual archive of documents and sources relating to the migration experience of the Irish people from the 18th century onward.

British Convict Transportation Registers Database

Around 160,000 convicts from Britain and Ireland were transported to Australia between 1787 and 1867. This database from the State Library of Queensland contains details of 123,000 convicts. It was compiled from British Home Office records.

Note: the link to the actual database is in the “Further information” paragraph at the foot of the page.

Happy researching!

Please pin a pin to Pinterest:

Leave A Comment