A mistake often made by family historians, especially new ones, is to assume that the information on official records was always correct. The majority of records will be accurate. However, a significant minority of vital records, census returns etc. contain inaccuracies. This article looks at reasons why there may be secrets, lies and errors in genealogy records.

This post uses British records as examples, but similar reasons will exist for errors in other countries.

Transcription errors in genealogy records

Transcription errors are probably the most common. In the days before copiers and scanners, copies were made by hand.

At an English church wedding (from 1837 onward), for example, three copies of the marriage record would be made:

- The event would be recorded in the Parish Register

- A copy would be made in another ledger for the local Registrar’s office

- The actual marriage certificate for the couple would be completed.

Then, every three months, copies of all the marriages in the previous quarter would be made and sent to the General Register Office in London. Each time a copy was made, there was a chance for an error.

These days, handwriting recognition software is used to quickly transcribe old documents by the big database companies. But handwriting styles vary and mistakes in transcriptions happen. Here’s an example from my own family tree:

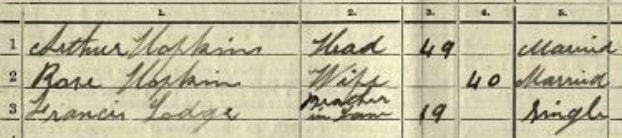

Extract from the 1911 Census showing the Hopkins household

This shows my great grandparents Arthur and Rose Hopkins on the 1911 census. Also in the household is Francis Lodge, Rose’s younger brother. His relationship to Arthur is correctly recorded as brother-in-law. However, Ancestry’s transcription recorded Francis as Arthur’s mother-in-law! This has since been corrected.

A close look at the record shows that the “B” in “Brother-in-law” does look a bit like an “M”. So, it’s understandable that the software made the error. This shows that it’s always best to find and check original documents.

Recording errors in genealogy records

Names

Most people couldn’t read or write until the end of the 19th century, so names were written on documents by officials or by church ministers and they often wrote down what they heard. Or how they thought names should be spelt. A surname like “Wright”, for example, may have been spelt “Rite”, “Right” or even “Royte”.

My great grandmother, Martha McGowan, sometimes had her first name recorded as Matilda. I’m guessing that this was because when she pronounced her name in her Ulster Irish accent, her name sounded like “Mata”. Officials maybe assumed she’d said “Matilda”. A tip here is to pronounce a name in your ancestor’s accent and see what other names sound similar.

First names often have variations and will be written in different ways. A child christened “Elizabeth” may appear on other documents as “Eliza”, “Liz”, “Lizzie”, “Beth” or “Bessie”.

Nicknames may be recorded instead of Christian names. My aunt, for example, was known by everyone as “Nan”, but she appeared on all official documents with the name she was christened with; “Annie”.

Ages

Recorded ages on documents were often inaccurate. Ages on the 1841 British census were listed as reported up to the age of 15 and then rounded down to the nearest 5 for adults in most cases.

Very often people wouldn’t know exactly how old they were. So, it’s often useful to give some leeway to reported ages, especially if the other facts on a document look right.

Birthplaces

You’ll often find birthplaces recorded wrongly on census returns. It’s possible that some of your ancestors might not know exactly where they were born or assume that they were born in a place where they grew up. Agricultural workers, for example, would often move around chasing work. So, the place of birth on a census return might be different to an actual birth or baptism record.

Here are a couple of things that aren’t recording errors, but are worth mentioning here:

You may find that a Baptism is not where you expect it to be. Sometimes, children would be baptized in the parish where the mother grew up. This could be many miles from where a family was living at the time. This was more common in Ireland than in Britain.

Another thing to look out for, especially from the 20th century is that it became much more common for births to happen in hospitals. In Britain, births were registered where the child was born, not where the parents lived. This could often be in a different registration district. If you can’t find a birth where the parents were living, look in neighboring districts.

Lies in the records

Very often there are omissions and even downright lies on official documents. The most common untruths, especially on census returns, are recorded ages. You’ll often see that some people don’t seem to age the full ten years between censuses. Women, especially would often shave off a few years as they got older.

This is often true where there was a big age difference in a married couple. The gap seems to diminish as they got older. When someone’s death occurs well into old age, the informant may have understated the deceased’s age by 10 or more years.

Attempts are often made to cover up “illegitimacy”. An unmarried mother may say that she is a widow on her child’s birth certificate and give a false surname. This may or may not be the name of the father. On census returns you’ll sometimes see the grandparents of an illegitimate child claiming to be its parents. The child’s actual mother will be recorded as its sister.

For more on this see: How to Deal with Illegitimate Ancestors

Sometimes, “social climbing” may explain reasons for untruths. This example from my own tree highlights this:

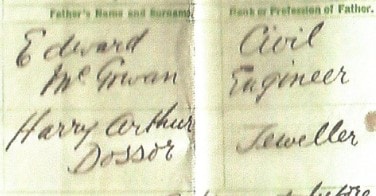

1938 Marriage Certificate extract

This is from a 1938 English marriage certificate. The couple’s parents are listed as Edward McGowan, Civil Engineer and Harry Arthur Dosser, Jeweler. The problem is that Edward was actually a retired dock worker and definitely not a civil engineer. The groom was marrying into a middle-class family and it looks like he may have been ashamed of his roots.

Sometimes you’ll come across an untruth that is difficult to explain. Here’s another example from my own tree:

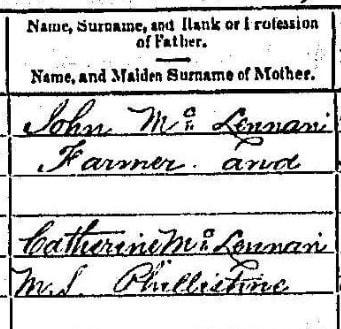

1884 Marriage record extract.

This is from an 1884 Scottish marriage record. In Scotland, the names of both parents are shown on civil records. Here we have the groom’s parents, John McLennan and Catherine McLennan, maiden surname Philistine. But Catherine’s maiden name was actually Finlayson, not Philistine! What’s going on here?

Maybe when the minister was completing the record, John said “this is my wife Catherine; she’s a philistine!”. The minister may have assumed that he meant that that was his wife’s name. We can only guess.

But it all goes to show that we can’t assume that official documents are always correct. It’s advisable to find other evidence that supports the facts recorded.

For more tips see the following:

Tips for Breaking Down British Genealogy Brick Walls

10 More British Genealogy Tips

28 Reasons why your Genealogy Research may be Stuck

10 Genealogy Research Tips I Wish I’d Known at the Start

For further reading, I recommend Helen Osborn’s book Genealogy: Essential Research Methods.

Happy researching!

Please pin a pin to Pinterest:

Hi, is there a place that one can look for, for German records like this. I am trying to find my great grandfather and I can’t find any records of him.

Hi Maya,

A good place to start is the German Genealogy Wiki on Family Search: https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Germany_Genealogy

You can also see a list of the German record sets available on FS as well as some learning courses here: https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/location/1927074?region=Germany

All of the above is free. Good luck with your research!

Alistair