Knowing where your ancestors are buried can provide valuable information about your family history. It can also help you connect with your roots and gain a deeper understanding of your family’s past. However, finding the grave of an ancestor can be a daunting task, especially if you don’t know where to begin. This article aims to help you find a grave using various records and websites.

Why you should look for a grave

Finding the graves of our ancestors can yield useful clues to our family history. For example, Sean’s family had always thought that her direct ancestor, Honora Egan had died in Ireland. However, after a bit of searching we actually found her grave much closer to Sean’s home in the US.

Sean next to the grave of Honora Egan, Vermont, USA

As well as allowing Sean to visit Honora’s grave, it opened up a whole new avenue for research.

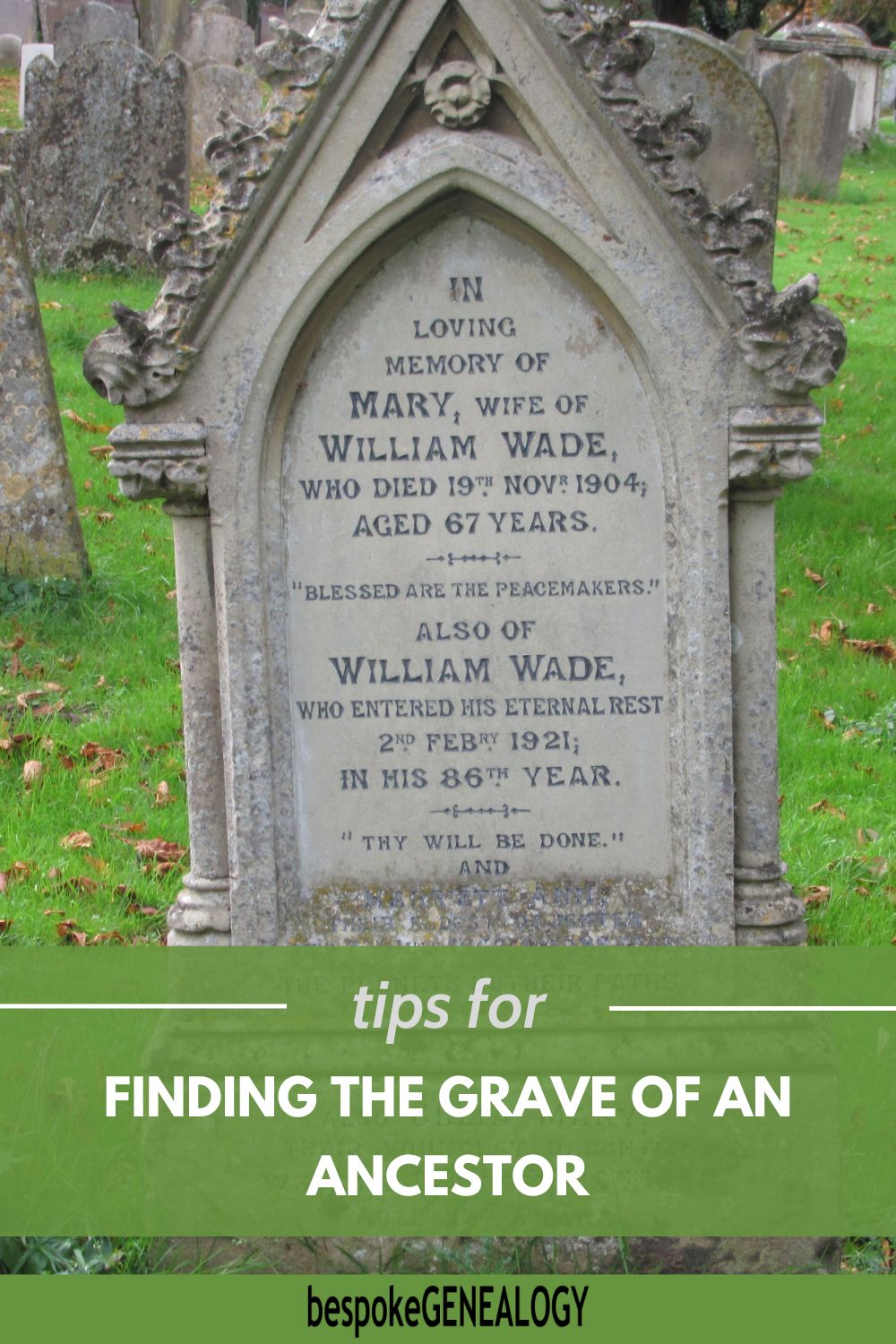

Often, other family members are buried in the same plot and recorded on the same gravestone:

Grave of Mary Wade and family. Eaton Socon churchyard, Bedfordshire, England

Here Mary Wade was eventually joined by her husband, William and two of their children. This information can be very helpful if vital records are difficult to get hold of or are missing.

If family members are not sharing the same plot, they are often buried close to each other:

Gravestones of Thomas and Sarah Salisbury, Easton churchyard, Huntingdonshire, England

Here, Sarah Salisbury is later joined by her husband, Thomas.

Sometimes, a trip to a graveyard can lead to an unexpected surprise, like finding this headstone:

Fiddler’s Grave, Castlecaldwell, Enniskillen, Ireland (National Library of Ireland)

This picture is from the National Library of Ireland and shows the Fiddler’s Grave at Castlecaldwell, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland. The inscription reads:

- To the memory of Denis M’Cabe, Fidler who fell out of the St Patrick Barge belonging to Sir James Caldwell Bart and Count of Milan, and was drowned off this Point Aug. 15, 1770

‘Beware ye Fiddlers of ye Fiddler’s fate

Nor tempt ye deep lest you repent too late

You ever have been deemed to water foes

Then shun ye lake till it with whiskey flows

On firm Land only – Exercise your skill

There you may play and safely drink your fill’.

Of course, you should be aware that even if you find a burial record, there is no guarantee that you’ll find a grave. Many people were buried in unmarked graves. Also, even if there was a headstone at the time of burial, it may have become unreadable over time, or moved or even vandalized. In some cases, the whole gravesite may have disappeared altogether to make way for a new road or for some buildings.

What are the different types of burial grounds?

There are basically three main types of historical burial ground:

- Church graveyard. In Europe at least, church graveyards were the most common type of burial ground until the 20th Usually, the established churches had a monopoly on burials and most people were buried in the grounds of the local church.

- Municipal or private cemetery. The industrial revolution led to the rapid growth in the population of towns and cities. As a result, many church graveyards in urban areas reached full capacity by the late 19th In addition, religious freedoms meant that some people did not want to be buried by the established church. This all led to municipalities creating their own large cemeteries. In some countries there are also privately owned cemeteries, but they perform the same function as those owned by municipalities.

- Military cemetery. If someone died in military service, they were usually buried in a large military cemetery, often overseas close to a battlefield. Although naval personnel who died in battle, were likely buried at sea.

In addition to the above, there are also:

- Family graveyard/vault. The European aristocracy were often buried in vaults in private chapels on their own estates. Family graveyards were also common in the early European colonies, especially before churches were established in settlements.

- Prison graveyards. Many prisoners, especially those that were executed, were buried in the grounds of the prison.

Records to help you find a grave

Before searching the grave database sites, it’s a good idea to try and find a record that actually states where your ancestor was buried. These are the main resources to look for.

Civil death records

In most areas, civil deaths (along with births and marriages) began being recorded in the 19th century

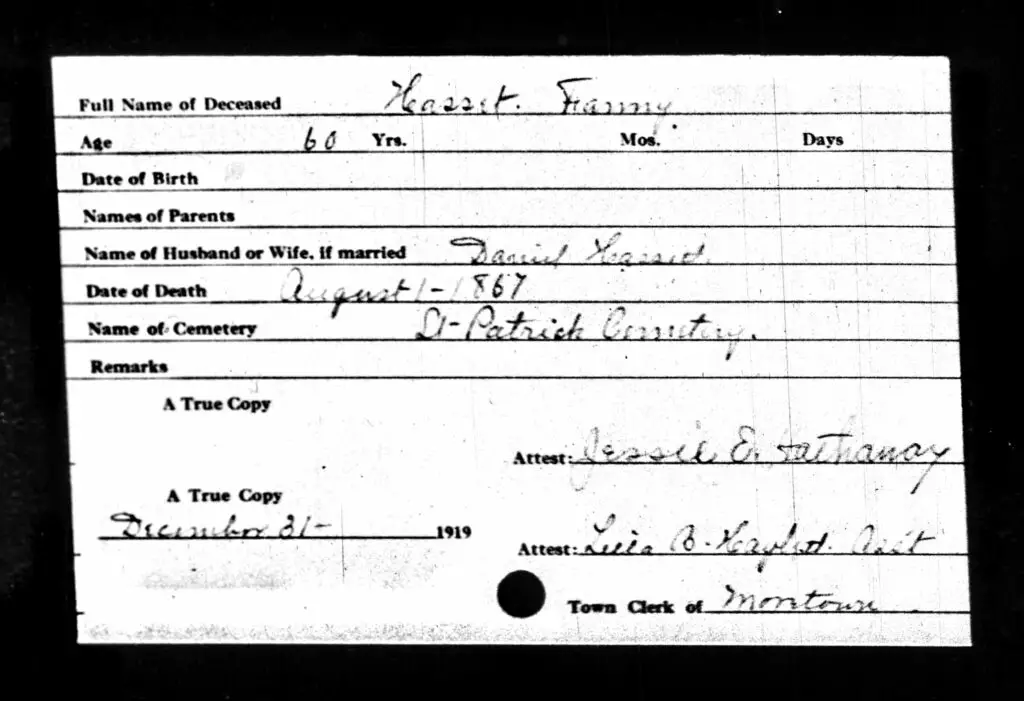

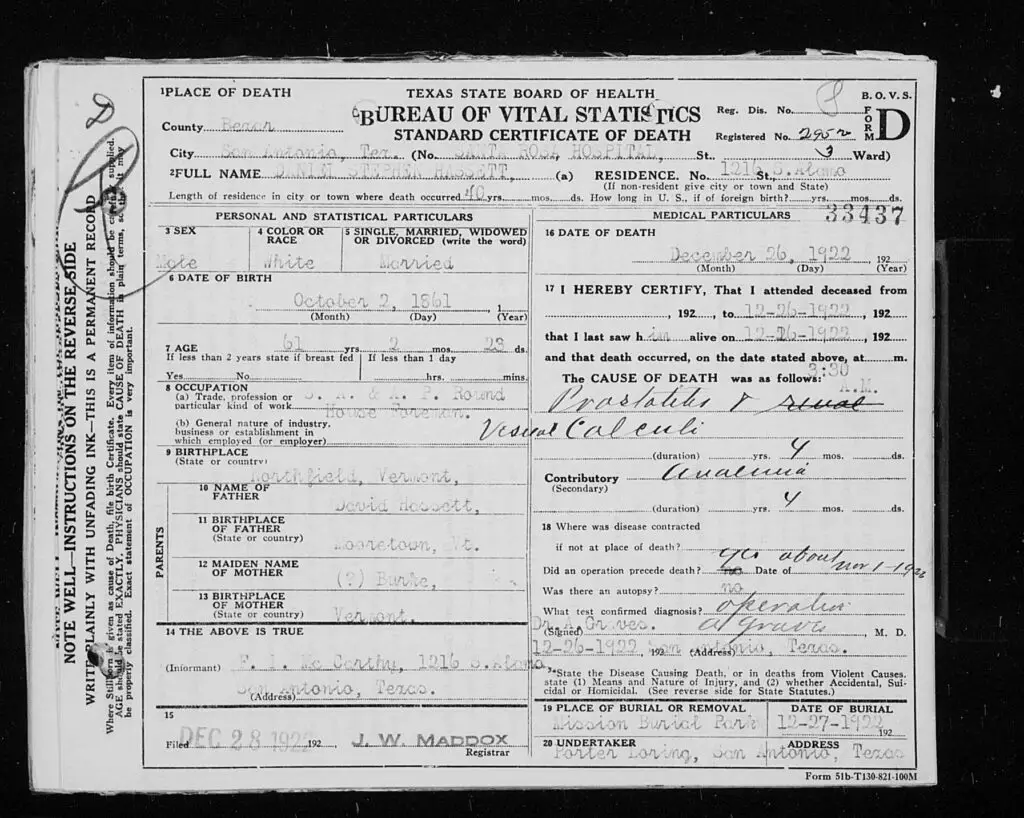

In some jurisdictions, a death record is also effectively the burial record. The place of burial will be written on a death record, as these examples show:

Death record of Fanny Hassett, 1 August 1867, Moretown, Vermont

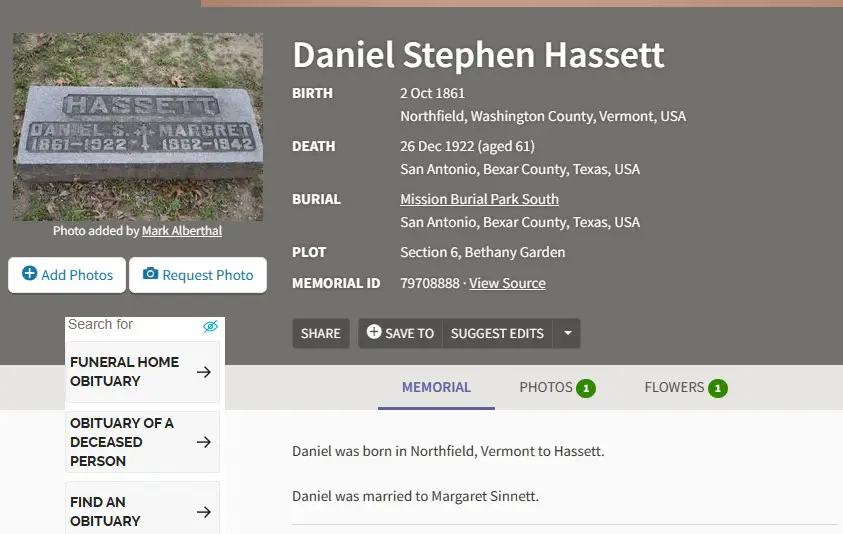

Death record of Daniel Hassett, 26 December 1922, San Antonio, Texas

However, in many areas a burial place will not be recorded on a death record. In the UK, for example, only the place of death is recorded. This is still useful to know as burials were usually (but not always) in the same area, at least if the person died close to their home.

To find a death record in your country/state/province/county, a good place to start looking is the Family Search research wiki. You can drill down to your area and find links to the records you need. You can also go to these pages for England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

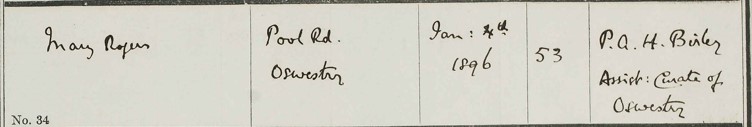

Burial Records

If a death occurred before civil registration was introduced, or if burial details were not recorded on a death record, then you should look for an actual burial record. If you find this record, then you’ll obviously know where your ancestor was buried. In many areas, these records can be harder to find than civil death records. And in Ireland, many records were lost in the 1922 fire in the Public Records Office.

Burial record of Mary Rogers, 4 January 1896, Oswestry, Shropshire, England

Church records (including burials) in many areas go back much further than civil ones. In England, Wales and Scotland for example, records in many parishes survive from the 16th century.

Cemetery burial records usually show similar information:

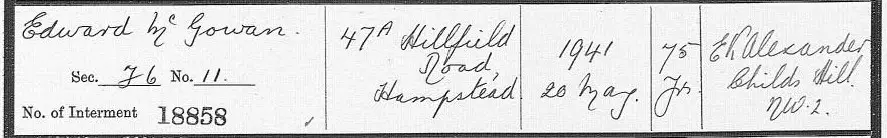

Burial record of Edward McGowan, 20 May 1941, Hampstead, London

The example above is the burial record of my grandfather, Edward McGowan. He was buried in Hampstead Cemetery in London which is owned by the local borough. Even if the burial was in a municipal or private cemetery, there was often a religious ceremony performed.

The last box on the form shows who performed the ceremony. In this case it was EK Alexander of Childs Hill. After a Google search, I was able to discover that Mr. Alexander had been the pastor at the Childs Hill Baptist Church at the time. So, this church was likely the one my grandfather attended.

Some burial documents, like Edward’s, will show the location of the grave which can be very handy.

Again, the best way to look for burial records is to use the Family Search Research Wiki. You can also use my parish register pages for England, Wales and Scotland to locate church burial records in these countries. See also my previous post: Where to find British and Irish Burial Records.

Newspapers

Historic newspapers can be really helpful in finding a grave as this example shows:

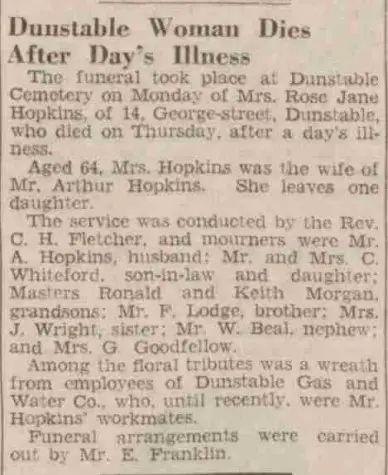

Newspaper clipping from the Luton News of 2 March 1939, announcing the death of Rose Lodge

This clipping is from the Luton News in 1939 and is the funeral announcement of my great grandmother, Rose Hopkins. Not only does it give the name of the gravesite (Dunstable Cemetery), but it also includes a lot of other useful family information.

There is also another example in the same edition of the Luton News which shows why using newspapers can be essential:

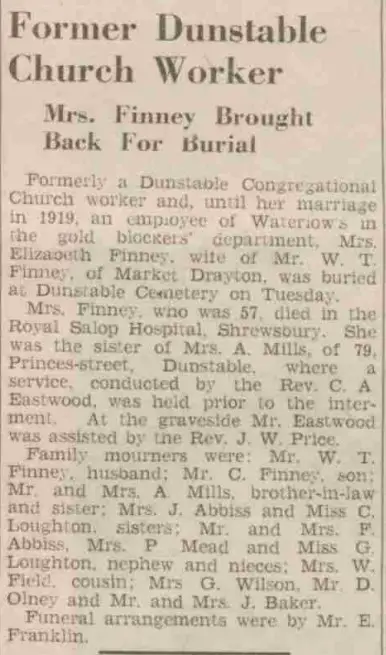

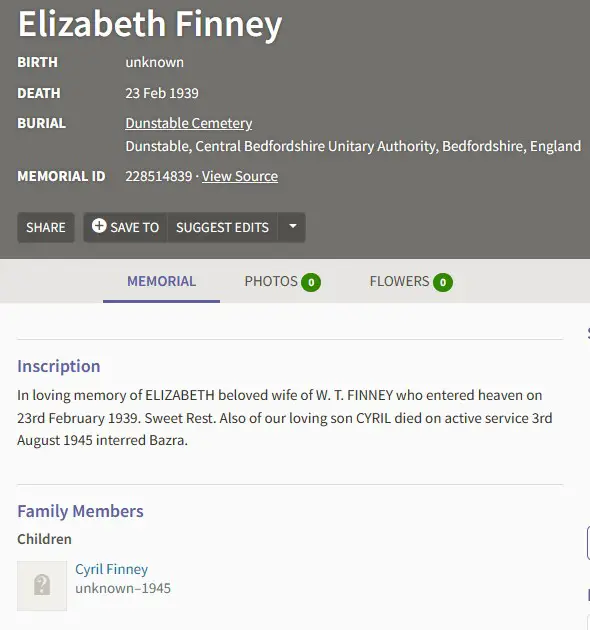

Newspaper clipping from the Luton News of 2 March 1939, announcing the death of Elizabeth Finney

This is the funeral announcement of Mrs. Elizabeth Finney who was also buried in Dunstable Cemetery. According to the clipping she died in a hospital in Shrewsbury and her residence at the time of death was Market Drayton (in Shropshire). If you just had Elizabeth’s death record, you would assume that she would have been buried in the Market Drayton area. Finding the newspaper announcement would therefore save you a lot of time and avoid a fruitless search in Shropshire.

Use the Family Search Research Wiki to find local newspapers. Also see the following articles:

- Find your British and Irish Ancestors in Newspapers

- Where to find Free Online Historical Newspapers

- Find Your Irish Ancestors with Online Newspapers

Military Records

If your relative served in the military, then his or her military service record may have survived. If they died in service, then this should be recorded in the service record. There may also be other records that record deaths, such as casualty lists.

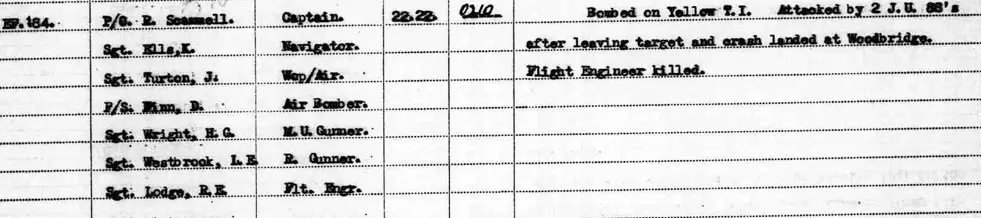

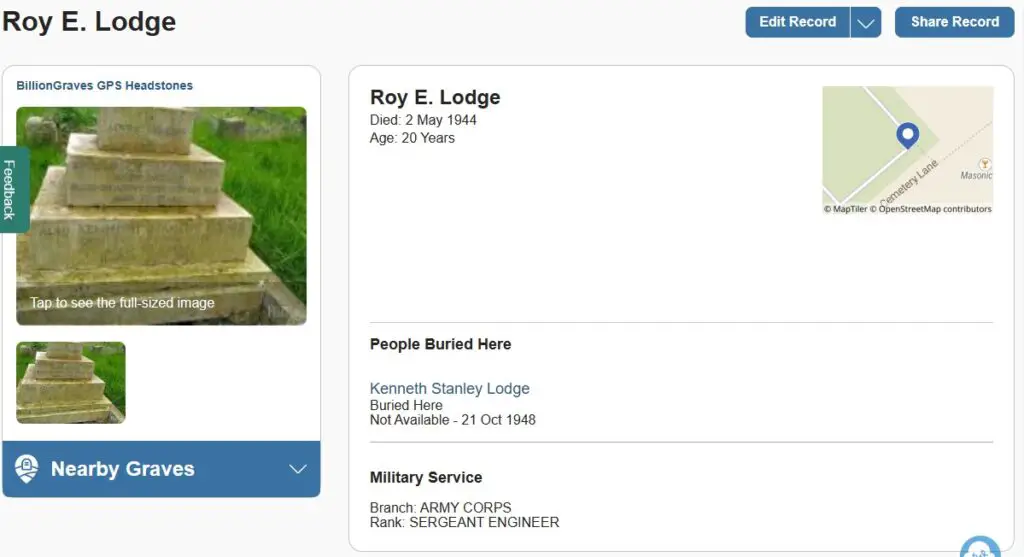

As an example, my cousin, Sgt. Roy Edward Lodge was a flight engineer in the Royal Air Force and was killed when his bomber was shot at by the enemy on 1st May 1944. This is recorded in the Operations Record for that flight:

Extract from the RAF Operations Record mentioning the death of Sgt RE Lodge, 1 May 1944

From this record, I can see that the aircraft crash-landed in Woodbridge which is in Suffolk, England. I can then look for his grave (see Commonwealth War Graves below). This extract is part of a record which was downloaded from The Genealogist. This record set is also available on the National Archives website.

The Family Search Research Wiki can lead you to military records in your area of interest. See also Where to find British & Commonwealth Military Records.

Prison Records

If someone died in prison, he or she was usually buried in the prison grounds. Often death was the result of execution as this record from 1820 demonstrates:

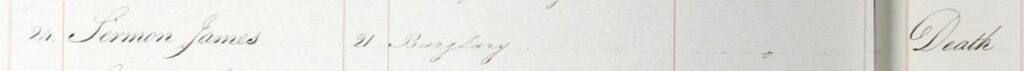

Part of the Prison Record of James Sermon, sentenced to death for burglary, 1820

This extract is from a prison record (from The Genealogist) and lists James Sermon who was sentenced to death in 1820 for burglary. The sentence was carried out in Newgate Prison, London.

Use the Family Search Research Wiki to find crime and punishment records for the area you’re interested in. See also Where to find British Crime and Punishment Records.

The Main Grave Finding Websites

Many graves are now online (often with pictures of headstones) on one or more of one of the grave finding websites. Ideally, you’ll find the burial site of your ancestor through the resources listed above. You can then look to see which website shows graves from that gravesite. If not, you can search for a person on the website and hopefully find them that way.

Find A Grave

Find A Grave is the largest grave finding website, with 226 million memorial records. Although owned by Ancestry, it is still free to use.

If you know the name of the gravesite, I recommend finding it first by clicking on CEMETERIES on the main menu. This is the entry for Elizabeth Finney (mentioned in Newspapers above) who was buried in Dunstable Cemetery in 1939.

Screenshot of the Find A Grave entry of Elizabeth Finney

In this case, there is no photograph of the headstone, but there is a transcription.

If you don’t know the cemetery or church, you can also search by name and approximate year of death. Which is what I did with Daniel Hassett’s death in 1922 (see death record above):

Screenshot of the Find A Grave entry of Daniel Hassett

If there is a long list of names, you’ll need to narrow your search by area and then go though each one until you find yours, if it’s on the site.

Billion Graves

Billion Graves uses searchable GPS cemetery data and, like Find A Grave, all the information comes from volunteers. The site is mostly free to access, although there is a paid upgrade with some extra features available. You will need to set up a free account to view individual grave data.

Like Find A Grave, you can search by person or cemetery. Searching for Roy Lodge who died in 1944 (see military records above) we can find his grave in Dunstable Cemetery:

Screenshot of the Billion Graves entry of Roy E Lodge

Interment

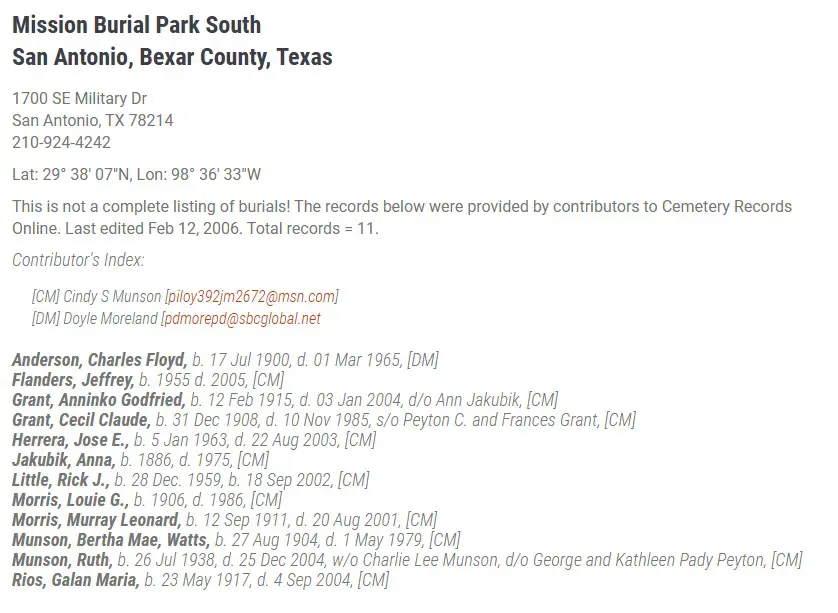

The other large grave locating database site is Interment. This site has over 25 million grave records. If you know the cemetery, you can drill down to see if there are records. This is the result for the Mission Burial Park South Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas:

Screenshot of the Interment entry of the Mission Burial Park South Cemetery, San Antonio, Texas

There are no pictures of gravestones, just transcriptions of basic information, although this can still be quite helpful.

Looking for an individual is not as easy as on the other two sites as only basic search is available.

Military Cemetery Websites

If your ancestor died while serving in the army or air force, he or she will probably be buried in a military cemetery. If he or she was from a Commonwealth country, the site to search is Commonwealth War Graves Commission. For the US military, see the Veterans Affairs Gravesite Locator.

Naval personnel who died at sea will probably have been buried at sea.

If you can’t find a cemetery on these sites, then it is always worth while just using a search engine to find it. You can then see if records are available online.

Monumental Transcriptions

Another source of gravesite information that is often overlooked is the book of monumental transcriptions.

Front cover of the Monumental Inscriptions book for Eaton Socon, Bedfordshire, England

These books are usually a complete set of transcriptions of all the gravestones in a particular graveyard or cemetery at a particular time. Often these were compiled many years ago, sometimes a century or more ago. The benefit of this is that many graves are recorded that have since been lost for various reasons.

The monumental inscription books were usually compiled by family or local history societies. Many societies offer scans of these books for sale as PDF downloads or on CDs.

To find a society, use the Family Search Research Wiki. You can also find contact details for family history societies on these pages for England, Wales and Scotland.

You can also search on the Internet Archive. As an example, this is a book of monumental inscriptions for the cathedral in Hereford, England, published in 1881.

For other sources of free online books see: Where to Find Free Genealogy Books.

Happy researching!

Please pin a pin to Pinterest:

Leave A Comment